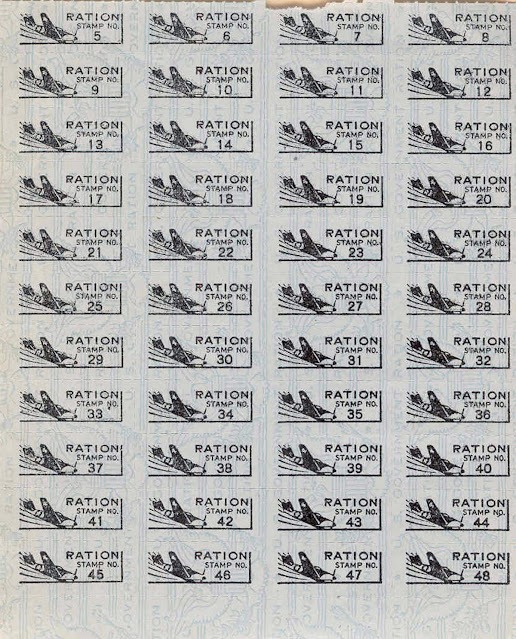

devoted four columns to an official U.S. government statement on footwear. Effective February 9, the statement explained, Americans would need a special coupon to buy a pair of shoes. Everyone would receive three of these coupons per year. Shoe rationing had arrived.

Rationing was a fact of life during World War II. The military effort churned through huge amounts of meat, dairy, sugar, tires, gasoline, nylon, and other staples. To guarantee consumers access to essential products at reasonable prices, the U.S. Office of Price Administration (OPA) distributed coupon books that set careful limits on everyone’s consumption. No coupon, no sugar — or shoes.

![]()

|

| These young ladies are trying on some white models at a store on Delancey St., on lower East Side, New York, 1943. |

![]()

|

| A number of people crowd into a shoe store on the last day for War Ration shoe coupon, June 1943. |

Shoes were rationed because leather and rubber were in short supply. (Rubber especially, as Japan controlled Southeast Asia, where the bulk of the world’s rubber was produced.) Hoping to avoid serious shortages, the OPA set a cap on shoe purchases, and issued new rules about the kinds of shoes that manufacturers could make. Only four colors were permitted — “black, white, town brown, and army russet” — and two-toned shoes were prohibited. Further disappointing the nation’s snazzy dressers, the OPA banned boots taller than 10 inches, heels taller than two-and-five-eighths-inches, and “fancy tongues, non-functional trimmings, extra stitching, leather bows, etc.” The resort set felt the pinch, too: men’s sandals and golf spikes were deemed inessential, and discontinued.

There were some exceptions. If you lost your shoes in a flood or fire, or if they were stolen, you could, mercifully, apply for a special certificate to buy a new pair. Mail carriers, police officers, and others whose work was hard on their feet were also exempt. Allowances were made for orthopedic and maternity shoes and a few other cases. Otherwise, the three-pair limit stood firm, but the OPA figured it was better than the alternative: compelling manufacturers “to produce shoes that would be so unattractive that people would not buy them unless absolutely needed.”

![]() |

| A World War Two US ration booklet. |

![]()

|

| Three models showcasing shoes made from material that is not being rationed during WWII, Chicago, Illinois, USA, 1944. |

The program did not go uncriticized. Rather than waste their coupons, consumers were buying shoes they didn’t need. Rationing had given rise to “the greatest shoe-buying orgy in the history of the nation,” the Times huffed.

In time, people found creative ways — not always legal — to circumvent the ration book. For a price, less-scrupulous store owners might look the other way if a customer didn’t have a coupon, and enterprising brokers bought and sold coupons on the black market.

Second-hand shoe stores got a nice bump, and inventive manufacturers introduced shoes made from materials that weren’t rationed: mostly plastics, but also “pressed carpet, felt, old brake lining material and even reclaimed fire hose.”

![]()

|

| Shoe sales spurt on the first day of rationing, February 10, 1943. |

![]()

|

| Business doubled recently at a store on 92 Third Avenue that sells factory rejects and second hand shoes not affected by rationing. |

All told, shoe rationing lasted more than three years. When it concluded in late October 1945, more than a month after the war ended, OPA chief Chester Bowles called it “one of our most successful programs.”