Hollywoodland sign in 1924.

The Hollywood sign may be unique among American icons. It is a landmark whose white letters are familiar around the world as the prime symbol of the movies.

Day after day tourists with cameras wander into surrounding Griffith Park or troll up and down the streets for the Hollywood Hills, looking to position themselves for the best possible angle on the sign.

To moviegoers and so many others, the sign represents the earthly home of that otherwise ethereal world of fame, stardom, and celebrity – the goal of American and worldwide aspirations to be in the limelight, to be, like the Hollywood sign itself, instantly recognizable.

But in contrast with the Statue of Liberty or Mount Rushmore, the Hollywood sign doesn’t depict a human image, nor is it in the form of an immediately familiar object, like the Liberty Bell or the Washington Monument. It may signify a place, but it’s not the place itself.

Instead, it is a group of letters, a word on the side of a steep hill that, unlike so many other cherished sites, cannot be visited, only seen from afar. The Hollywood sign embodies the American yearning to stand out of the landscape

. It reflects the impulse to performance and singularity that has been a part of the American psyche since the US first appeared, unprecedented, on the world stage in the late eighteenth century.

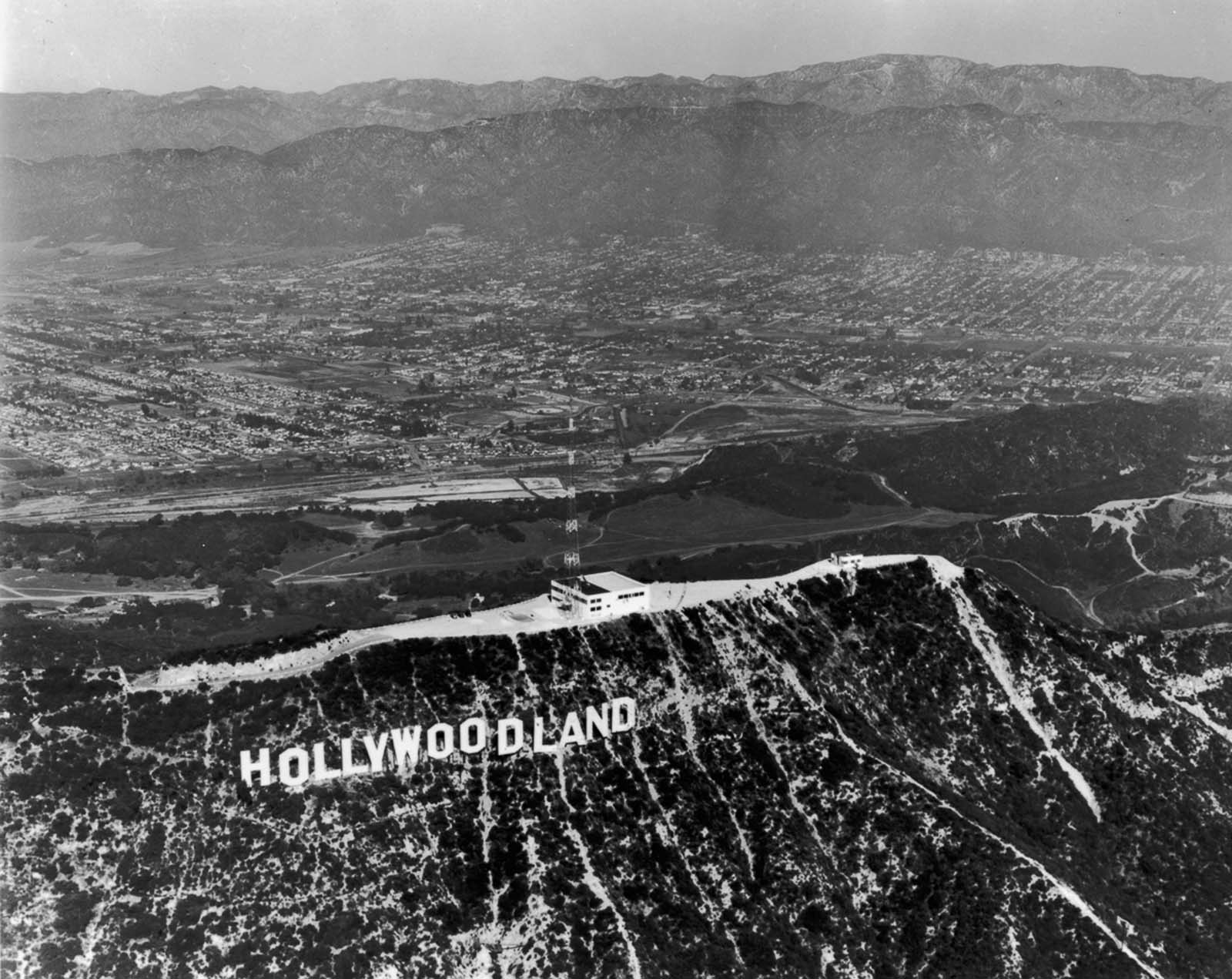

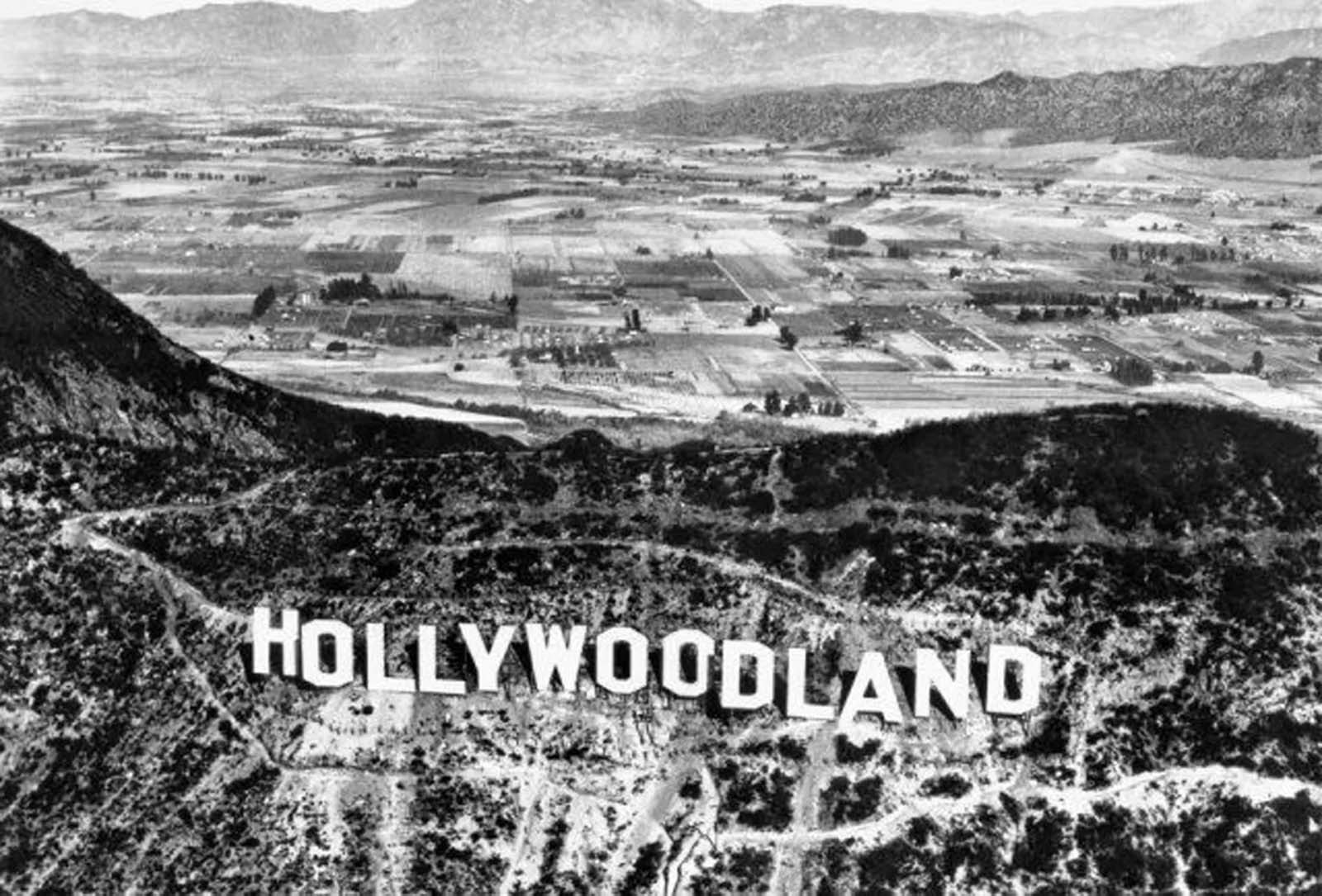

Surveyors and builders working on the Hollywoodland housing development pose for a portrait beneath the sign erected to advertise the site. 1923.

The sign was erected in 1923 and originally read “HOLLYWOODLAND”. Its purpose was to advertise the name of the new segregated housing development in the hills above the Hollywood district of Los Angeles.

Tracy E. Shoults and S. H. Woodruff, the developers, envisioned Hollywoodland as an elegant throwback to old California. The two men joined a partnership led by transportation moguls E. P. Clarks and M. H. Sherman and the Los Angeles Times publisher Harry Chandler to subdivide and develop property in Beachwood Canyon in the spring of 1923. Shoults died suddenly of a heart attack in July 1923, and Woodruff was promoted to head developer.

In April 1923, Shoults and Sherman hired architect John L. DeLario to oversee the Hollywoodland design team. DeLario also favored the look and feel of Spanish and Mediterranean homes in Southern California but updated them for more modern sensibilities.

He called this type of home California Renaissance. Architectural styles were limited to only four: English Tudor, French Normandy, Mediterranean, and Spanish.

The style was important; developers painted Hollywoodland as an elegant, exclusive enclave affordable to the middle classes. Details mattered as well; granite retaining walls, terraces, and stairs created a peaceful fairy tale ambiance, as did the storybook homes built into the area’s dramatic hills.

The Hollywoodland sales team was one of the first to recognize the value and importance of new media in promoting the project. They invited newsreel cameramen to record demolition and construction, formed radio bands to gain free advertising opportunities, invited equestrian groups to ride through the neighborhood, and created elegant rotogravure brochures.

The Hollywoodland sign in 1924.

The developers also understood the importance of creating a unique brand and quickly established one with their enormous calling card, the famous HOLLYWOODLAND sign.

They contracted the Crescent Sign Company to erect thirteen south-facing letters on the hillside. The sign company owner, Thomas Fisk Goff (1890–1984), designed the sign. Each letter was 30 ft (9.1 m) wide and 50 ft (15.2 m) high, and the whole sign was studded with around 4,000 light bulbs.

The sign flashed in segments: “HOLLY,” “WOOD,” and “LAND” lit up individually, and then as a whole. Below the Hollywoodland sign was a searchlight to attract more attention. The poles that supported the sign were hauled to the site by mules. The project cost $21,000, equivalent to $320,000 in 2019.

The sign was intended only to last a year and a half, but after the rise of American cinema in Los Angeles during the Golden Age of Hollywood, the sign became an internationally recognized symbol and was left there. The “Land” was removed in 1949 in order to reflect the district, not the “Hollywoodland” housing development.

Over the course of the decades, the sign, designed to stand for only 18 months, sustained extensive damage and deterioration but was designated a Historic-Cultural Monument in 1973 and rebuilt with more permanent materials in 1978.

The Hollywoodland sign at night, 1928.

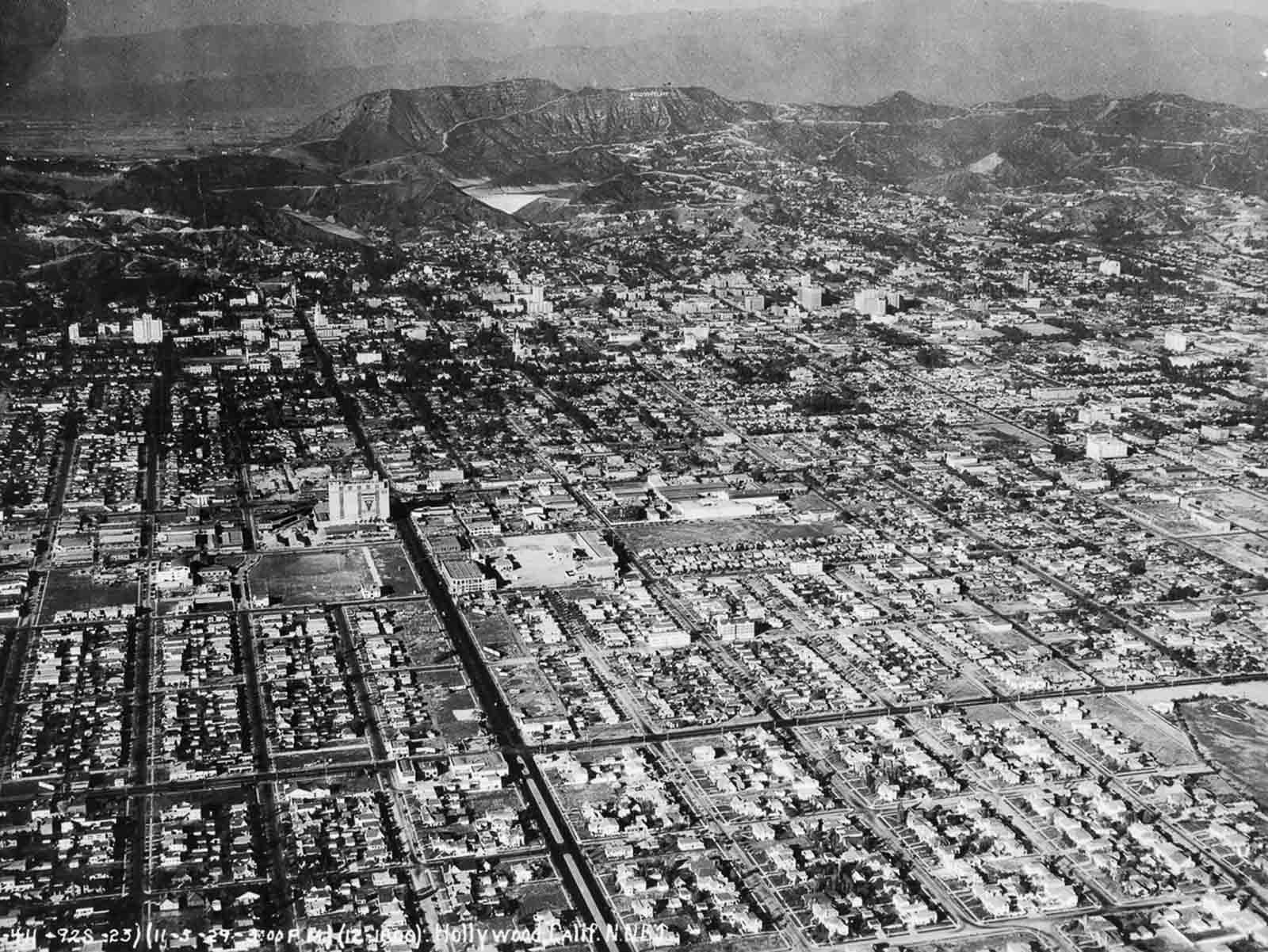

An aerial view of Hollywood, with the Hollywoodland sign in the background. 1929.

The sign in 1935.

The Hollywood sign in 1978.

A sweeping view of the Hollywoodland sign.

In this 1978 photograph, workers prepare to lower the last letter of the old Hollywood sign that had stood at the site since the 1920s.

The iconic Hollywood sign.

(Photo credit: Michael Ochs Archives / Underwood Archives / The Hollywood Sign By Leo Braudy / Hollywoodland By Mary Mallory).